The Lifespan of a Costume

Year in and year out, the 110 artisans in the Met costume shops are responsible for clothing the multitudes that fill the stage night after night—from Chinese ministers to Russian aristocrats to the humble inhabitants of Catfish Row. By Christopher Browner

“In one season alone, our team works on well over 2,600 individual garments,” explains Elissa Iberti, the Met’s former head costumer. And while a number of these costumes are constructed from scratch, many more were built decades ago. “Our goal is always to uphold the Met’s incredible standards while also being as economical as possible and working to preserve these pieces of company history,” Iberti says.

The intricately embroidered ceremonial robe below is worn by the Chinese minister Pong in the first act of Franco Zeffirelli’s spectacular production of Puccini’s Turandot—which returned to the stage most recently in October 2019. One of 294 costumes designed by Anna Anni and Dada Saligeri for the staging’s 1987 premiere, the piece was created using genuine antique Chinese textiles. Having now been worn by six tenors over more than 180 performances, it underwent a fair amount of pre-season refurbishment and careful maintenance.

Preparations for the 2019–20 season began eight months before Opening Night—while the previous season was still in full swing. Working from a master list of soloists’ measurements, a team of eight production supervisors, along with head drapers and pattern makers, decided whether existing garments would fit the upcoming cast or if the department needs to create new builds based on the original designs.

This process of creating a “new-build list” lasts months, with racks and racks of costumes for each revival arriving from the Met’s costume-storage facility across the Hudson River. The team then focuses on preparing the reusable costumes for the stage—starting with the revivals opening in the first weeks of the upcoming season. The production supervisors carefully examine each garment for damage before sending it into the workroom for repairs. Depending on the level of maintenance required, a single piece may be worked on by six or eight people—from tailors to cutters to drapers to craftspeople and milliners—before making its way to a singer’s dressing room, ready for another turn in the spotlight.

Put a Pin in It

This safety pin marks a section of the embroidery thread that is coming loose. To avoid the thread snagging on anything during a performance, a stitcher will reposition, tack down, and mend this detail.

A Stitch in Time

The shoulders of a costume tend to experience the most wear and tear, so to avoid further damage, these areas have been heavily patched. But with this section layered under another robe, the audience will never be able to spot the artful repair work.

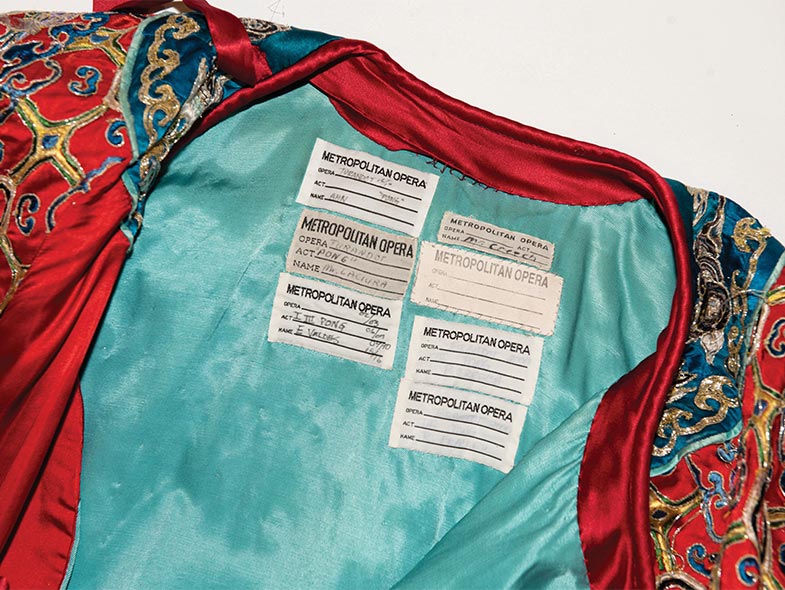

Hello, My Name Is ...

Every new singer to wear a costume receives a personalized label inside the garment. The tags are never removed during the life of the costume, so all six of the artists who have worn this piece can be tracked using these labels: from Anthony Laciura, who sang Pong when the production was new in 1987, to Eduardo Valdes, who first sang the role in 2002 and returned during the 2019–20 season.

Fine Print

Between a production’s premiere and the time when one of its costumes must be replaced, a specific textile may no longer be available. If that happens, as in the case of this blush-colored material, the Costume Department can digitally scan the garment in order to print a new fabric closely inspired by the original.

Pain in the Neck

Christopher Browner is the Met’s Associate Editor.

A performer’s blood, sweat, and tears—not to mention a generous dose of stage makeup—will leave their mark on any costume. Despite the Met’s diligent cleaning regimen, the collars of older garments acquire their fair share of stains over the years.