Friend of the Devil

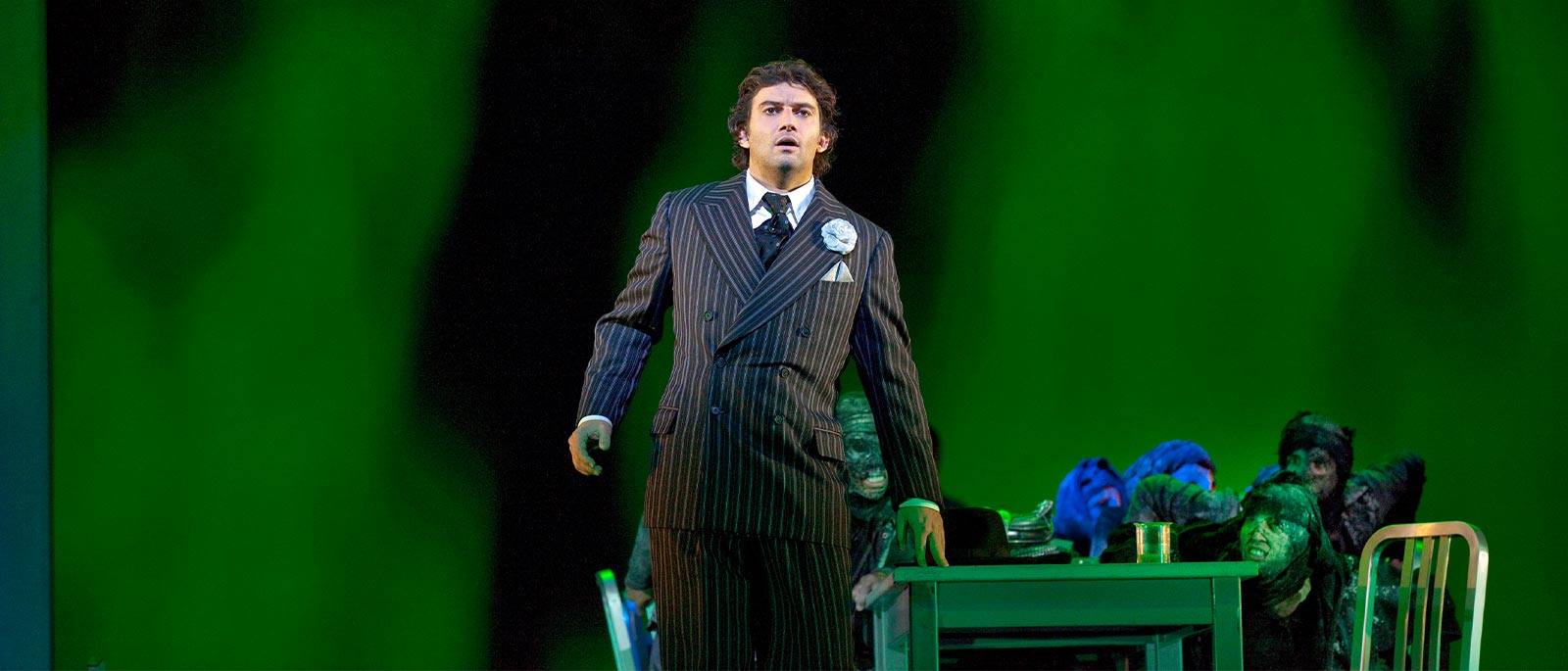

In the Met’s 2011 production of Gounod’s Faust, tenor Jonas Kaufmann starred as the hero whose quest for knowledge ends in tragedy. Director Des McAnuff reimagined the Faustian bargain with a dreamlike staging set in the first half of the 20th century. By William Berger

Gounod’s Faust, based on Goethe’s epic poem of the aging philosopher who sells his soul to the devil, was one of opera’s reigning favorites for many decades following its 1859 Paris premiere. Buoyed by the opera’s international success, Gounod was catapulted to the ranks of the most popular composers. When the Khedive of Egypt wanted to inaugurate his new opera house in Cairo with splendor, his agents were given permission to approach Verdi, Wagner, and Gounod—any of whom would suffice for the commission. (Verdi eventually created Aida from this starting point.) Faust was the opera that opened the original Metropolitan Opera House in New York in 1883, and for many years it reigned as the company’s most performed opera.

During the 2011–12 season, director Des McAnuff made his debut with a theatrical vision for Faust that set this timeless work in an entirely new historical setting. “While I’m fascinated by history and I’m a great admirer of this work,” McAnuff explains, “I’m interested in its pertinence to now. That’s what we’ve focused on with the singers and the designers. We’ve spent a lot of time making sense of Faust for today.” McAnuff and his designers chose the first half of the 20th century as the setting for the staging, using some of the images of that recent time as cornerstones of their account. “It starts at the end of World War II with the detonation of the atom bomb, and then goes back to Faust’s youth, which would be at the beginning of the First World War,” the director explains.

He had an extraordinary assemblage of artists to help him in this reimagining of the Faust legend. Yannick Nézet-Séguin was on the podium, with soprano Marina Poplavskaya as Marguerite, Faust’s romantic ideal, and bass René Pape as the devil Méphistophélès. Tenor Jonas Kaufmann sang the title role for the first time at the Met.

The director admits that, at first glance, the 20th-century setting might seem like an extreme departure from conventional ways of presenting the opera. But McAnuff sees a clear connection. “The events of Hiroshima and Nagasaki really changed the world forever. And I think the Faust legend prophesized that in a very pertinent way,” he says. “Faust has really learned everything. He’s acquired ultimate knowledge, which I think applies in a horrifying way to the nuclear bomb and our ability to destroy ourselves. And so I’m interested in the personal responsibility that goes into that, and I think that’s the Faustian journey right there.”

This journey, as McAnuff sees it, takes place both in a single instant and over time; the story is seen as an unfolding memory within the split second of the old philosopher’s suicide in his laboratory. “Faust essentially never leaves his laboratory, and the setting for the production has it transforming throughout the various scenes and acts of the story.” This single space, then, is a portal for memory, framing the very diverse elements of the opera. “The dramatic tone and the visual look of the third act is very different from the opening, which, in turn, is very different from the ending,” McAnuff says. He sees the diversity within the opera as an indication of the work’s strength, and the laboratory framework allows for the full expression of each different scene: “It all takes place in the same environment.”

The costumes also blend cohesion and fluidity. “There’s a very dreamlike quality to the production, and time moves in a somewhat jagged fashion,” McAnuff says. “The costumes are certainly inspired by the periods that we move through from World War I into the 1920s and ’30s through World War II, but they’re not obedient. Paul Tazewell, who’s a brilliant designer, has made the clothes as if they are a manifestation of Faust’s fantasy.”

Faust has not always enjoyed the lofty position it achieved a century-and-a-half ago. Musicologists have questioned its easily appreciated (too easily, according to some) wealth of melody. It has been severely cut by conductors and impresarios. And it has been scorned by literati who viewed it as a frivolous gloss on Goethe’s masterpiece of German literature.

McAnuff’s hope is to present an evening of drama worthy of the music. Gounod’s treatment of the Faust story, far from being a dilution of the legend, demonstrates the story’s inherent flexibility. The score, with its undeniable beauty and charm, is high French Romanticism, a style of rich sentiment that McAnuff embraces “in all its glory.” Gounod was writing for his contemporary audience rather than aspiring to impress Goethe’s readers or to compete with the many other opera composers who have flocked to this story over the ages. Consider the character of the devil Méphistophélès, so different in Gounod’s work from other operatic incarnations by Hector Berlioz, Arrigo Boito, or Ferruccio Busoni. While Boito’s Mefistofele, for example, thunders proud challenges to the Lord in Heaven against a musical background of stentorian choral antiphons, the evil of Gounod’s Méphistophélès is more human in scale: He sneers at a disgraced single mother while strumming a guitar and laughing obnoxiously. This devil is suave, urbane—you could even call him supremely, stereotypically Parisian. He must have seemed familiar to the French audiences for whom Gounod wrote his opera. He successfully—if scandalously, according to some—made the old tale something his contemporary listeners could relate to, which is what McAnuff intended to do with his new production.

The director’s relationship with the Faust myth runs deep: He grew up adoring a recording of the opera that his father (a French horn player) owned. He auditioned for the design program at drama school with a presentation of Christopher Marlowe’s 16th-century Doctor Faustus, yet another great literary rendition of the legend. McAnuff’s appreciation of Gounod’s score extends to the often-omitted Walpurgis Night scene, at once haunting and vibrant, which is presented in this production.

The fluidity of time and the price of the Faustian bargain also feature in the production, particularly in its portrayal of another important aspect of the opera: the love story. “Faust pursues innocence through Marguerite and, of course, ends up tainting that innocence—even by trying to relive it, he ends up maligning it, polluting it, destroying it.”

McAnuff believes that, if presented with vitality and vision, both Gounod’s score and the opera’s dramatic rendition of the Faust myth have the power to grip today’s audiences as tightly as they ever have. “I love this entire score. I think this is truly one of the great masterpieces of the middle part of the 19th century,” he says. “And I hope we’ll reach audiences at the Met, not just with the extraordinary score but with what I think is one of the great stories of all time.”

William Berger is a Met Radio Writer and Producer.