Technically Speaking

In the Met’s new production of Lucia di Lammermoor, the singers tackling Donizetti’s bel canto pyrotechnics aren’t the only ones being pushed to the limit. Simon Stone’s audacious present-day staging, which moves the action to a declining town in America’s Rust Belt, incorporates several innovative technical elements to tell Lucia’s story and conjure its setting as vividly as possible, and the Met’s backstage wizards are pulling out all the stops to make it happen. By Jay Goodwin | Photography by Jonathan Tichler

As the World Turns

The 57-footdiameter turntable built into the rear stage wagon has been a key part of the Met’s theatrical machinery since the Lincoln Center opera house opened in 1966, and has been used by numerous productions over the years. Normally, two or more scenes will be pre-set on different sections of the turntable, and it will be rotated to change the scene. In Stone’s Lucia, however, the turntable is used much more extensively to create not static scenes but an immersive environment, with characters moving from location to location within the town while it rotates in sync. In fact, for the entirety of Act I, the turntable never stops moving.

Under work lights, stagehands rehearse moving a large piece of scenery off of the turntable while it rotates.

To accomplish this, stagehands must continually roll large pieces of scenery onto and off of the turntable while it’s moving at varying speeds, timing everything precisely so that the right set elements arrive—safely—at the right place at the right time. To help achieve this, a graphic monitor that shows the turntable’s exact rotational position has been added to the stage manager’s desk so that he or she can call technical cues at just the right moment. The movement of the turntable must also be rehearsed carefully with the singers, who have to remain oriented as they’re whisked in front of and past the audience, and as they make their exits at very different places from where they entered.

The stage manager keeps track of the turntable’s position with a digital monitor.

Open Concept

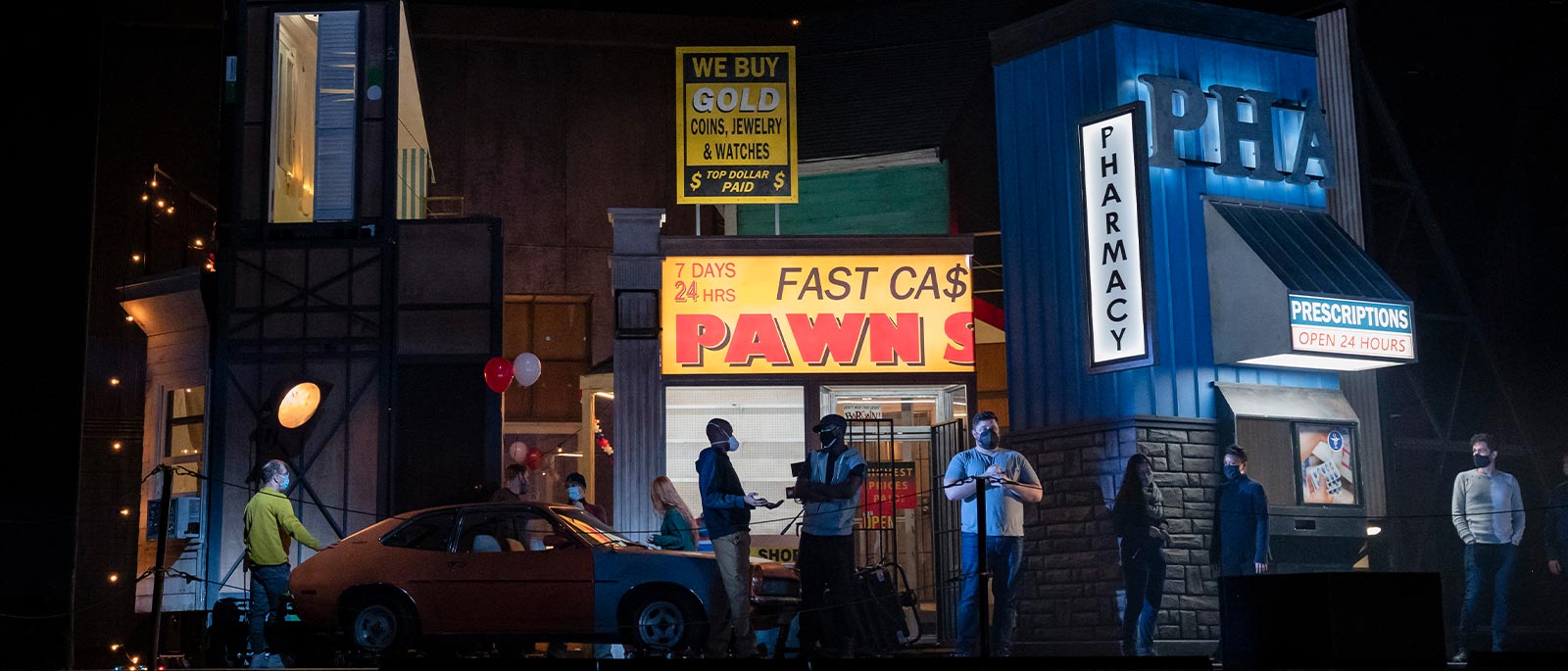

To make matters even more nerve-racking for the technical crew, Lucia uses no cyclorama or other masking, meaning that the Met’s entire, sprawling backstage area—including vast wings on either side of the stage and sometimes even the loading area at the rear, extending nearly to Amsterdam Avenue—is visible from the auditorium. This means that many scenery changes, lighting operations, and other normally unseen activities are done in full view of the audience, requiring the stagehands to be costumed and providing a unique opportunity to see them do their work.

The open nature of the set allows the audience to see into the vast backstage area and watch stagehands at work.

Stage and Screen

Perhaps the most immediately striking element of the production is the huge, 48 × 19–foot video screen spanning the full width of the proscenium above the stage, which provides additional perspectives on the action. Sometimes, pre-recorded video sequences allow the audience to see into Lucia’s mind: In the famous Act III mad scene, for example, when the heroine hallucinates her beloved Edgardo before her, the pair are seen together onscreen, while onstage below, Lucia is alone.

A huge screen above the stage shows live video footage during the performance, allowing for close-up views. In this rehearsal image from Act I, we zoom in on Nadine Sierra as Lucia.

More inventive, though, is the incorporation of live video, shot onstage as part of the performance and transmitted simultaneously to the screen above. Using this system, Stone is able to show close-ups, giving the audience a more intimate view of the characters’ interactions and emotions—and even of Lucia’s activities at moments when she’s not visible onstage. This zoomed-in perspective is also helpful in communicating some elements essential for maintaining the contemporary setting. For instance, the forged letter that Lucia’s brother Enrico traditionally produces to convince her that Edgardo has forsaken her has been updated to a doctored social-media photo of him with another woman, visible to the audience via a close-up view of a smartphone.

Large projectors in the auditorium beam video to the screen.

To capture the live video footage, two performers equipped with Steadicam rigs roam the stage framing the shots, while Met video experts in a control booth remotely adjust the technical settings, such as focus and exposure.

While Normanno (Alok Kumar), Raimondo (Matthew Rose), and Enrico (Artur Ruciński) perform a scene downstairs, a camera captures video of Lucia in her bedroom upstairs.

Mad Props

The contemporary setting also means that many props unusual for an opera company are required, and the close-up video footage means that all of the set dressing must be realistic down to the smallest details. Just for the Rust Belt town’s mini-mart, for example, the Met’s props team must arrange hundreds of individual magazines, bags of potato chips, candy bars, and various other wares for sale. They also had to fabricate a working conveyor belt for customers’ groceries. For the wedding scene, there are two banquet-size tents that have to be set up on the fly, along with all the decorations one would expect at such an event.

A Ford pickup truck is one of three real automobiles used in Stone’s production.

And this is not to mention the three real automobiles that make appearances—a Ford pickup truck, a Nissan Sentra, and a vintage Ford Pinto, all of which have been modified so that some of their parts can be easily removed onstage at Lucia’s family’s chop-shop. All together, it makes for one of the most intensive props shows in the Met repertory.

Jay Goodwin is the Met’s Editorial Director. Jonathan Tichler is the Met’s Photo Editor.